Broadridge’s SFCM team Martin Walker, head of product management, and Anupma Bakshi, senior business analyst, breakdown the key distinctions between centralisation and decentralisation and their role in the securities finance market

People have always had mixed views about centralisation. The classic medieval castle sitting on a hill above the town served as a reminder of the King’s ability to levy tax on residents, yet also provide safety from potential attacks. There are similar mixed feelings towards centralisation in capital markets.

Several years ago, there was a belief in a fully decentralised world, free from centralised infrastructure and financial intermediaries. First came the cryptocurrencies, but it turned out they needed centralised exchanges to allow trading between cryptocurrencies and conventional forms of money.

Then came decentralised finance (DeFi), much of which looked surprisingly similar to securities finance. To quote the OECD: “DeFi lending activities try to mirror market-based lending (securities lending, repos) rather than traditional consumer or retail bank lending, as most activity involves collateralised lending.”

Much of the DeFi world has become surprisingly centralised. DeFi businesses do not appear spontaneously. People and companies create and largely control them. On the other hand, DeFi has lacked most of the features of a good centralisation, notably someone to fairly enforce rules, and who can be held accountable if things go wrong and, in the worst case, sued. After the occurrence of many problems in the DeFi world, such as fraud and technical issues, intermediaries can indeed add a lot of value.

In the conventional financial world there are, and always have been, varying degrees of centralisation, whether measured in terms of technology, market structure or governance. A book by Ruth Wandhöfer and Hazem Danny Naki, titled Redecentralisation – Building the Digital Financial Ecosystem, looks at the messy reality of centralisation and decentralisation in the financial system. But what is the relevance of all this to stock borrow loan?

On one hand, the securities finance industry has seen over two decades of attempts to increase centralisation, both in terms of trading and clearing, but also attempts at removing intermediaries. On the other hand, there is increasing decentralisation by encouraging initiatives such as peer-to-peer trading. Even after all the investment in market infrastructure and technology, securities finance is still a combination of direct trading, via Bloomberg, phone calls, email, firm specific systems and centralised trading platforms. To think clearly about the value of further centralisation, or maybe more decentralisation, it is worthwhile to think about the dimensions of centralisation and decentralisation in capital markets.

Figure 1: Dimensions of centralisation in capital markets

Dimensions of centralisation

Centralisation in trading is not simply a matter of someone in the high castle telling everyone what to do, although that is one of the important aspects of centralisation. For each of these dimensions there can be varying degrees of centralisation. These dimensions may also be carried out by different parties. One organisation, for instance, may design market infrastructure, but another may operate that infrastructure. Areas such as trading and centralised management of risk (using central counterparties) are also typically managed by different parties.

Standard setting and governance — for markets to work effectively and efficiently, rules and standards need to be created. Stock exchanges, for instance, have been setting rules of conduct and business for hundreds of years. In the digital age, what is equally important are the standards for communicating and modelling data. Systems need to be able to talk to each other in a common language. Governance can be imposed by a central body or agreed collectively by participants but, even in that case, someone needs to perform a coordinating role.

Trading — markets, starting with physical markets, were created as places where the maximum number of buyers and sellers could come together. Bringing the benefits of open competition, increased market liquidity and transparent price discovery.

Post-trade — the end result of any trading process is the transfer of ownership of securities or funds. The infrastructure for settlement can to varying degrees be centralised and to varying degrees integrated with, or controlled by, trading venues. There are also a group of other post-trade processes that happen after the execution of a trade, such as confirmations and the management of trade lifecycle events.

Regulation and compliance — if you have rules, someone needs to enforce them. Potentially this will be those operating a market or a third party such as a regulator or a central bank.

Risk management — the processes of trading and settlement creates market, credit and operational risk to varying degrees for both the marketplace and the participants. One of the key methods for managing risk is to use a central counterparty (CCP). As indicated by the name, CCPs are inherently centralised and the greater the proportion of the market clearing trades via a CCP (despite the concentration of risk), the greater their ability to stop a cascade of firm failures bringing down the whole market.

Infrastructure design, implementation and operation — the capital markets today are largely digital, so somebody needs to design and build the technology. Some providers of centralised markets are as much technology firms as they are financial firms. In other cases, the firm running a market may outsource most of the process of designing and building financial market infrastructure.

Trading centralisation — equities vs securities finance

Equities trading is a great illustration of how the different dimensions of centralisation can interact with each other. Equities trading generally involves a CCP that takes credit risk during the settlement cycle. In some countries, such as India, the CCPs are owned by the exchanges. The existence of a central counterparty does not just mitigate risk, it also facilitates anonymous trading. In India, the electronic limit order book that matches orders almost completely removes market makers from the picture — an interesting example of centralisation reducing the need for other market intermediaries.

Vertical integration of centralised services, such as trading and settlement, can also reduce the various types of communications, booking and operational errors that are major factors in driving settlement fails and other post-trade costs. Centralisation of trading in a single venue also maximises market liquidity and price transparency.

While some equity markets are highly centralised and vertically integrated, regulators have pushed varying degrees of decentralisation in some markets. In Europe, the US and the UK, vertical integration of markets and settlement infrastructure is discouraged, if not banned. There has also been a proliferation of trading venues, driven by regulators’ desire to increase competition. This has created concerns about the potential reduction in market liquidity from market fragmentation, ie decentralisation of trading.

The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has described this debate as “intense”. At least for pricing, the problems of decentralisation in the equities markets are addressed through measures including the introduction of “consolidated tapes”, real-time price feeds that consolidate prices for the same securities from multiple venues. While this has been a concept in place in the US since the 1970s, there is growing support for this approach in the UK and the EU.

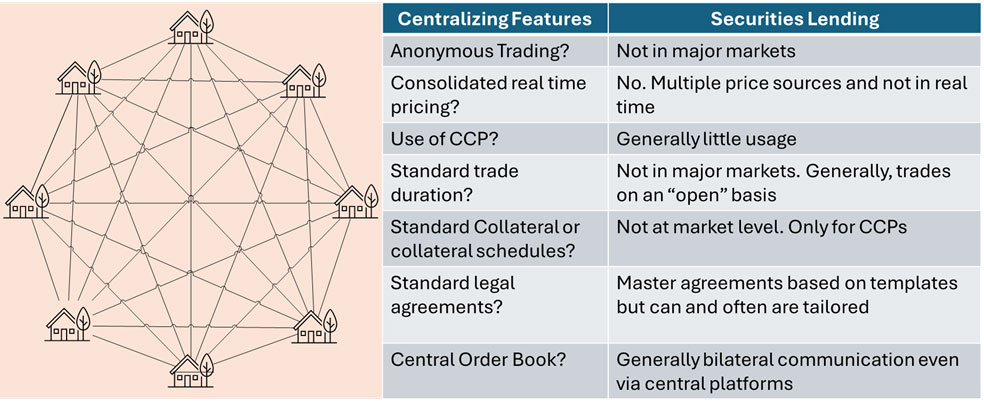

Figure 2 - The forces of decentralisation in securities finance

In securities finance, centralised platforms add a great deal of value. Centralised platforms for both trading and post-trade services bring:

• A high degree of standardisation in terms of communications

• Automation in the routing of orders to lenders or borrowers and availability to borrowers

• Improvements to market discovery

• More transparent pricing for trading on individual platforms — but this is not market level price transparency

• Support for trading across multiple jurisdictions

• Tools for making indications of interest across relevant counterparties

Despite this, the securities finance industry and its platforms retain characteristics which make it, by most dimensions, highly decentralised, particularly in the trading process. This is illustrated in Figure 2. This means relationships and personal networks continue to play an important role in the market, despite participants potentially missing out on a more liquid, demand and supply driven competitive market.

Conclusion

Over several decades, most asset classes in capital markets have followed a path towards greater standardisation, transparency, use of central clearing and general centralisation — a trend generally driven by regulators. Securities finance has already been pushed along this path by regulations in Europe such as the Securities Finance Transaction Regulation (SFTR) and Regulation 10c-1a in the US. There is still a long way to go before securities finance looks like other markets.

If collateral requirements become standardised, trade durations become standardised (and fixed) and clearing becomes compulsory, it will then complete an evolution to a model more closely resembling cash equities. In some markets, the operation of the securities lending market is already closely integrated with the local stock exchange.

This process may potentially take decades. In the meantime, it is possible that the market may even see some degree of decentralisation. Many of the benefits of centralisation that are achieved in cash equities are not present in centralised models of securities lending. If the costs do not fully justify the benefits, we could see a period of change.

To be prepared, regardless of which direction the market goes, firms will need to have an internal infrastructure that gives them the flexibility to deal with either greater centralisation or greater decentralisation. Internal systems — whether in-house or provided by a vendor — will still need to provide the foundations for effective trading. These include the flexibility to integrate with multiple internal or external systems, as well as providing a real-time view on inventory based on close integration with post-trade systems or with custodians..