10c-1 reporting: SEC reopens consultation

01 March 2022

In the second of two articles, Bob Currie evaluates the SEC’s 10c-1 proposal to promote transparency in US securities lending

Image: stock.adobe.com/erphotographer

Image: stock.adobe.com/erphotographer

In late November, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) announced a new US trade reporting regime that it expects to bring greater transparency for the securities lending industry.

The proposals, which were unveiled by the SEC under Exchange Act Rule 10c-1, require lenders to report the material terms of securities lending transactions to a registered national securities association (RNSA), along with details of securities on loan and available for loan.

The first part of this article, published two weeks ago in SFT 296, provides detail of the proposed 10c-1 reporting framework and the reaction of the industry during public consultation, which closed on 7 January.

It is noteworthy, as we go to press with this issue, that the SEC has voted to reopen public consultation, providing respondents with additional time to share their recommendations on the design of the Proposed Rule. This additional consultation window will extend until 1 April (or 30 days from its publication in the Federal Register, whichever is later), giving respondents roughly one month to file their comments.

This is broadly equivalent to the first round of public consultation, when the SEC put forward 97 questions in its consultation document but gave the industry just 30 days to respond. The decision on Friday to open a second consultation window is indicative of the strong body of feedback received during the first consultation period and the weight of unanswered questions raised by the initial 10c-1 design.

Under the proposed new rule, any person that loans a security on behalf of itself or another person will be deemed to be a “lender”, including banks, insurance companies and pension plans, and thereby required to report.

To track the transaction, the RNSA will be required to assign a unique transaction identifier to each reported securities lending trade. Under this Proposal, the RNSA will publish selected data relating to each transaction, along with any subsequent modifications. It will also publish aggregated data providing details of on-loan securities and securities that are available to loan.

Scope and (extra)territoriality

Respondents to the SEC consultation highlight that further clarification is needed regarding the territorial scope of the 10c-1 reporting obligation and, also, which transactions should be reportable.

Although the Proposed Rule states that ‘(a)ny person that loans a security on behalf of itself or another person’ has a reporting obligation, the Rule in its current form does not identify clearly whether it is the lender’s domicile, the security itself or a combination which brings a transaction into scope of the reporting regime.

By comparison, under the Securities Financing Transactions Regulation (SFTR) regimes in the EU and UK it is primarily the domicile of the transacting entities which determines the reporting obligations, such that an EU entity, or an EU based branch of a non-EU entity, is required to report (or the equivalent for UK application).

According to Adrian Dale, head of regulation, digital and market practice at the International Securities Lending Association (ISLA), ISLA was advised that up to 18 per cent of lender transactions in the US market are provided by funds outside of the US. This statistic implies that a considerable volume of activity may not be captured by the proposed regulation, pending clarity on scope and extraterritoriality.

When a regulator is driving for greater transparency, as the SEC is doing with 10c-1, ISLA indicates that it is important, as far as possible, that these regulatory provisions are fit for purpose worldwide. This demands co-operation and agreement between national supervisors. Without this, inconsistencies are likely to develop in how markets are regulated at national level which could create arbitrage opportunities and impair efforts to harmonise around common global standards.

Thomas Tesauro, president of Fidelity Capital Market — speaking on his company’s behalf as a principal lender, borrower, prime broker, lending agent and securities lending data provider — shares concerns that the extraterritorial scope of the Proposed Rule is not clear.

He also indicates that the Proposed Rule does not define accurately what it means to “loan a security”. Fidelity is one of a number of respondents to the 10c-1 consultation that urges the SEC to provide clear definition of when a securities loan is deemed to be “effected”, pointing out that in the marketplace a loan is not typically considered to be effected until the loan has been contractually booked and settled, which may be end-of-day or on T+1.

Lessons from SFTR

In 2013, the FSB published a report, Policy Framework for Addressing Shadow Banking Risks in Securities Lending and Repos, that set out recommendations to address financial stability risks relating to securities financing transactions (SFTs). These included recommendations for national supervisory authorities to improve data collection for SFTs, strengthening their ability to detect financial stability risks and to develop policy responses.

Given that the EU has implemented a trade reporting regime for SFTs through a phased implementation during 2020 and 2021, it is useful to explore whether the SEC can learn valuable lessons from the design, testing and implementation process for SFTR.

Speaking to SFT, ISLA’s Adrian Dale indicates that had there been a market standard data representation of securities lending prior to that regulation, SFTR’s implementation would have been significantly faster, it would not have required years of consultations and clarifications, and would not have demanded as much development effort by market participants. At the same time, it would have offered regulators a clean view of the relevant SFT markets.

ISLA recommends that the support of a market-derived data set should be considered, both to facilitate transparency proposals and to assist the market in its future development. The Association has been working with its members, and with the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) and the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA), to create a consensus-derived market data standard, the Common Domain Model (CDM), which has been widely discussed elsewhere in SFT. Dale indicates that ISLA has made itself available to the SEC to discuss any of these points, including development and wider application of the CDM.

The 10c-1 Proposed Rule appears to envisage a much ‘leaner’ reporting framework than SFTR, with 12 reporting fields in the current 10c-1 design, compared with 155 for SFTR.

SFT asked Fran Garritt, RMA director of securities lending and market risk, whether this ‘lean’ 10c-1 reporting template is suitable for meeting the SEC’s transparency objectives — and whether additional fields may need to be added to provide a more accurate picture in terms of pricing transparency. Read Fran Garritt's article in full here

Garritt responds that RMA does not favour adding additional fields to the 10c-1 template. “We believe the SEC will be able to capture all the pertinent information related to pricing transparency with the current proposal,” he says. “From RMA’s perspective, excess data fields add limited benefit considering the additional cost of sourcing and transmitting the additional fields.'' In making this point, Garritt reminds us that the scope of 10c-1 and SFTR are quite different. “10c-1 would implement statutory authority for rulemaking with respect to securities lending specifically,” he says, “while SFTR covers other kinds of transactions.”

For ISLA’s Adrian Dale, it seems highly likely that the SEC will need to add additional fields during implementation to achieve the full objectives that it intends through the reporting regime.

“Experience [from SFTR implementation] illustrated that the initial field template advanced by regulators to support the reporting process is unlikely, in practice, to be sufficient — and typically it will be necessary to add extra fields during the testing and implementation to capture any missing elements,” says Dale. As an example, additional fields may need to be added to capture ESG and sustainability considerations in lending strategy and collateral transfers.

With this in mind, ISLA has continued to host meetings since SFTR went live to find solutions to data issues. For example, its members continue to encounter issues with fields and events such as timestamps, settlement failure, trading venue, maturity date, fees and Legal Entity Identifiers (LEIs). Questions may also be driven by conflicts between primary regulation, subsequent regulatory clarifications, and market practice.

As illustration, Dale notes that SFTR only has one currency field, for example, even though there may potentially be different currencies for valuation, collateral, and billing, and this consequently requires some workarounds to communicate the required information. Although currency fields are not a good example for the US market, Dale indicates that this does highlight the potential drawbacks inherent in the historical approach to regulatory reporting.

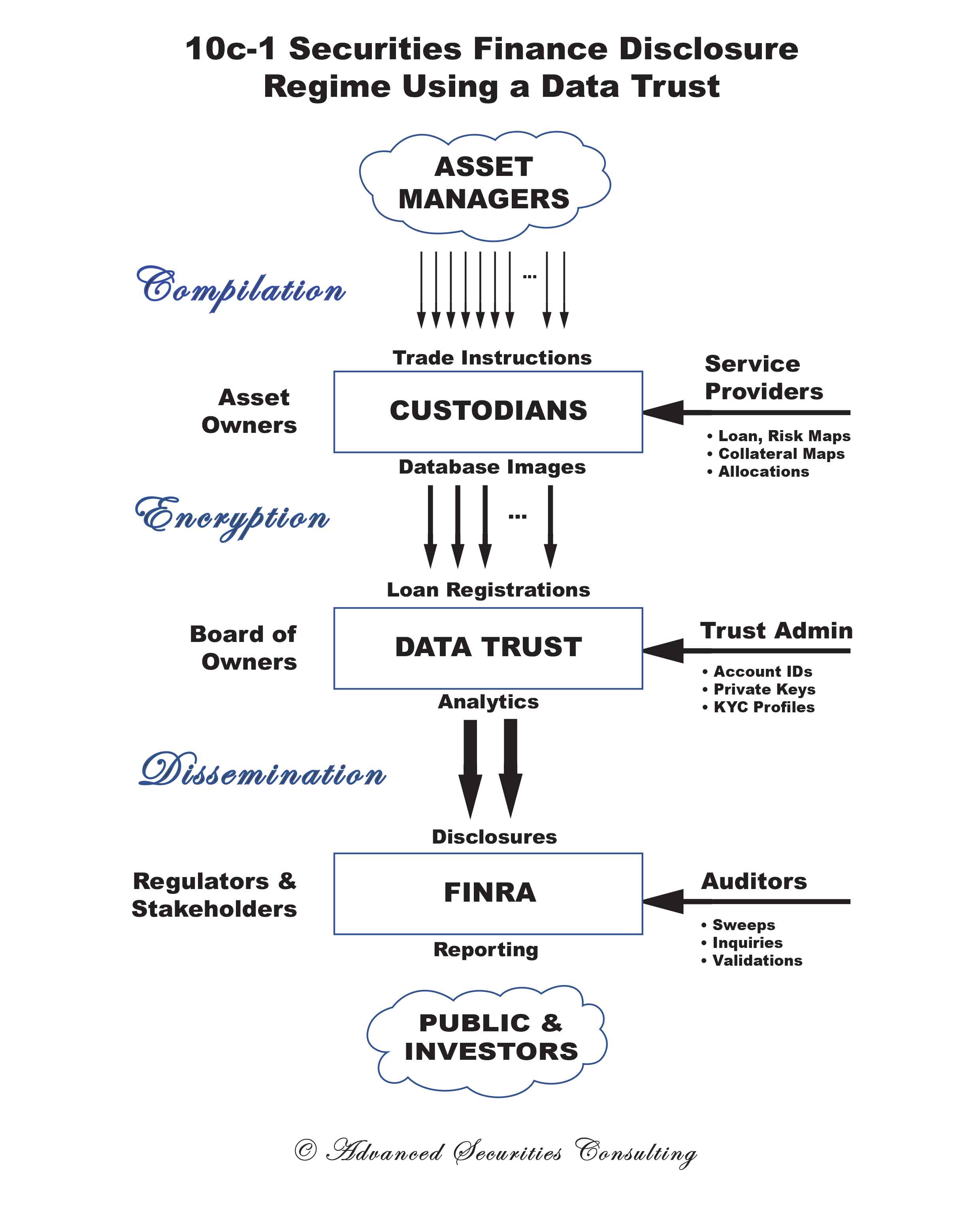

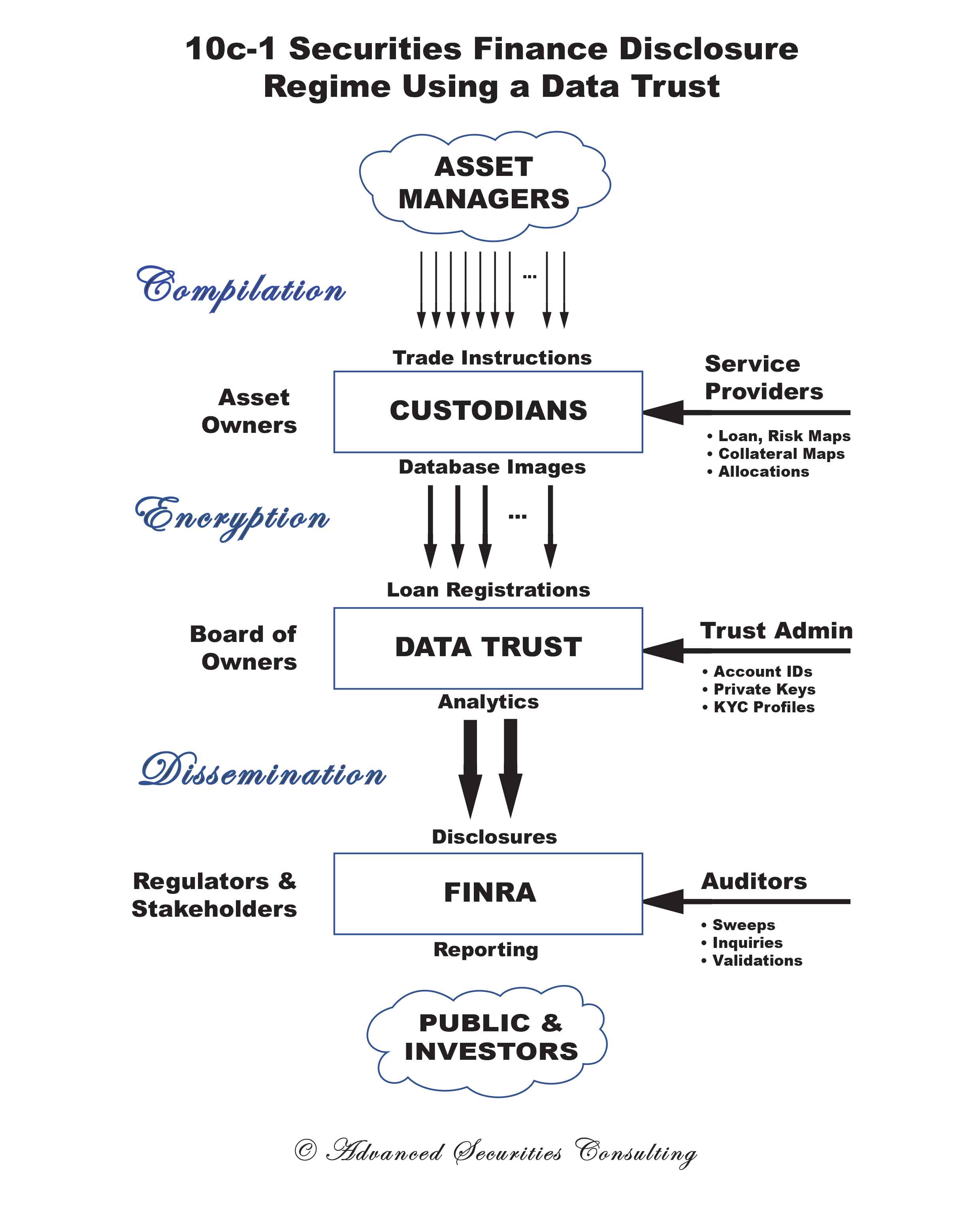

Ed Blount, in his capacity as executive director of Advanced Securities Consulting, proposes an alternative to the SEC’s proposed 10c-1 design that will allow asset managers to report loans to an RNSA via a registry using a copy of the custodian’s records (fig 1).

Figure 1

Speaking to SFT, he advises allowing lenders to report from their own data trust — a database that could be serviced by custodians on behalf of lenders and which, potentially, could be managed on a permissioned blockchain.

Under the data trust arrangement (box below), asset managers will submit trade reports to the beneficial owners’ custodians and carrying brokers; and agent lenders will submit loan transaction details or delivery orders to the custodian, as they do currently. The custodian will then send a copy of designated master files to the data trust registry, marking this with a unique transaction identifier (UTI) generated by the custodian’s systems.

Data trust

Ed Blount and David Schwartz, from the Centre for the Study of Financial Market Evolution, outline the case for a data trust to support securities lending reporting

A data trust is an evolving mechanism for individuals to take the data rights that are set out in law (or the beneficial interest in those rights) and to pool these into an organisation, a trust, in which trustees would exercise the data rights conferred by the law on behalf of the trust’s beneficiaries. The central organising principle for every data trust is that the trustees are instructed to use the data assets for the owners’ exclusive benefit. The key features of a data trust are ownership and control.

Blount and Schwartz recommend that the 10c-1 reporting system outlined in the SEC’s proposal should be adapted to accommodate a data trust formed by beneficial owners in the securities lending industry. Although a data trust for securities lenders and borrowers would be an original application of the concept, Truata, the European Mastercard data trust, may provide a useful precedent. Truata was formed to anonymise customer transaction data for analysis and compliance with the EU’s consumer privacy regulations. Truata’s beneficiaries are competitors, just like securities finance market participants, so they rely on robust usage and encryption policies that make it difficult for owners to use the data as a weapon against one another.

If lenders were permitted to join together to form a data trust, Blount and Schwartz believe they could pool not just the information required by 10c-1, but also Know your Customer (KYC), proxy voting, ESG and other transaction data for their own benefit.

This would offer potential to produce all the publicly available data envisaged by the SEC, as well as a privileged dataset of highly confidential, shared analytics for the reporting lenders, who are expected to pay for the 10c-1 disclosure system.

Data vendors and fintechs would bid to service the registry database, enabling beneficial owners to benefit from the analytics provided by these vendors, as they do currently. Contractors would reformat records and facilitate 10c-1 reporting to the regulatory transaction repository, as today. The creation of a new, wider pool of data would also stimulate competition among data vendors – which is another SEC goal.

If, as a 10c-1 requirement, the SEC continues to require data on loan availability (see box on p 20), Blount believes this can be captured accurately by the data trust from the portfolio custodian’s master files. However, some beneficial owners are likely to insist on their LEIs being encrypted and inventory aggregated to avoid providing information that might tempt predatory traders.

Corrections and modifications to reported loans — as well as data on ‘locates’ — could also be reported from the custodian’s master files in the data trust.

According to Blount, at least US$100 million could be saved from the estimated US$375 million in projected start-up costs for 10c-1 reporting, given that custodians are connected to the lending agents and asset managers through a number of utility networks. Instead of the 409 data input pipelines to FINRA, as estimated in the proposal, Blount says that only two would be needed for lenders of participating asset managers.

In developing an effective reporting regime, ISLA’s Dale emphasises that it is important for financial regulators to keep a watchful eye on the opportunities extended by new technology and harmonisation.

From a technology standpoint, he suggests that a reporting system based on distributed ledger technology (DLT) may deliver a more effective solution than the current SEC 10c-1 design. In a DLT-based environment, trade and collateral data may be reconciled instantly by trading parties (or their reporting agents), providing financial regulators with a transparent, consolidated view of market pricing in near to real time in accordance with the goals of 10c-1.

In implementing this solution, ISLA believes it is advisable to migrate to a DLT-based data repository, rather than adopting an intermediate solution — such as the SEC 10c-1 Proposal — that will consume resources and will potentially delay the adoption of an innovative DLT-based solution.

Delegated reporting

The SEC’s 10c-1 Proposal envisages a single-sided reporting regime that makes provision for reporting to be delegated to broker-dealers by lenders, subject to a written agreement. This currently appears to be the only form of delegated reporting permitted by the proposed rule. Beneficial owners that do not employ a lending agent or enter into a written agreement with a reporting agent would be responsible for complying with the requirements of the proposed rule themselves.

From a buy-side perspective, the Investment Company Institute (ICI) urges the SEC not to limit permitted lending agents to banks, clearing agencies, brokers or dealers for the purpose of meeting 10c-1 reporting. It should instead permit any lending agent that serves as an intermediary to a securities loan transaction to report on behalf of a beneficial owner, providing that it is able to satisfy the requirements defined by the Proposed Rule. “We believe that expanding the Rule in this manner would facilitate reporting by beneficial owners that prefer to use non-broker-dealer lending agents to report their securities loans,” say ICI’s associate general counsel Sarah Bessin, and Susan Olson, general counsel.

A broad set of reporting agents are supporting the SFTR reporting process in the EU and the UK — some of which are data or technology vendors and do not meet the SEC’s 10c-1 requirement of being a bank, agent lender or broker-dealer. Consequently, the SEC may wish to broaden its set of approved reporting agents, recognising that some lenders with international activities may prefer to utilise the same agents to manage their 10c-1 reporting in the US.

For Sharegain’s CEO Boaz Yaari, it does not follow that, just by virtue of being a broker-dealer, an entity will have the technological capabilities to meet the reporting challenges under the Proposed Rule. Therefore, where such technology capabilities exist, allowing Qualifying Technology Agents to act as reporting agents under Rule 10c-1 would ease the burden on broker-dealers and avoid concentrating the reporting services market.

Pirum indicates in its consultation response that the proposal to allow reporting to be delegated via a registered broker-dealer may create potential confidentiality and conflict of interest issues, as often the lenders subject to the reporting requirements will be engaged in securities lending with the same broker-dealers that they also use for transactions in the cash markets.

Without an alternative, Pirum believes, beneficial owners would either be forced to build their own direct reporting to RNSAs to mitigate these concerns, thereby significantly increasing their costs, or to exit the market entirely, thereby reducing overall liquidity.

Available-for-loan securities

SFTR in the EU and the UK requires two-sided reporting of SFT transactions with the objective of strengthening regulators’ and market participants’ ability to monitor risk across securities lending and financing activities.

However, in driving for greater transparency in securities lending markets, the SEC’s 10c-1 proposal requires that lenders report details of securities lending transactions on a trade-by-trade basis, and also provide additional information on securities that are on loan or available to loan.

As discussed more fully in part 1 of this article, this data for securities on loan and available for loan must be submitted to the RNSA by the end of each business day.

A number of respondents to the SEC consultation argue that the requirement to report available-to-lend securities should be removed from the reporting process.

The Risk Management Association states, for example, that requiring lenders to report securities that are available to lend “would provide little or no significant benefit for the securities lending market” — and this may potentially discourage lending and use of reporting agents.

RMA’s Fran Garritt and Mark Whipple, chair of the RMA’s Council on Securities Lending, point out that other securities finance transaction reporting regimes, particularly SFTR, do not require lenders to report data on available-to-lend securities. They propose that, in the case of 10c-1, more accurate estimates of loan supply could be extrapolated from fluctuations in trading volumes and fees that will also be available to the SEC through data that it aims to collect through the 10c-1 reporting regime.

Other observers note that the Proposed Rule mandates reporting of total on-loan balances, securities available to loan and the utilisation rate, but does so without regard to whether the lender has self-imposed restrictions on the number of securities or percentage readily available to loan. In this case, disclosing loan balances and utilisation rate, but without accounting for lender restrictions, is unlikely to provide a useful benchmark of availability.

Respondents from buy-side trade associations also raise concerns that the proposed 10c-1 reporting regime may reveal confidential information about members’ trading strategies.

Jennifer W Han, chief counsel and hedge of regulatory affairs at the Managed Fund Association (MFA), says that the MFA is “strongly concerned” that transaction-by-transaction financing data, even in anonymised form, would “provide the market with sufficiently detailed information to allow market participants to reconstruct or reverse-engineer investment and trading strategies, leading to situations similar to the GameStop and AMC market events.”

Jirí Król, deputy CEO and global head of government affairs at the Alternative Investment Management Association (AIMA), explains that even in anonymised form, these disclosures, specifically regarding the fee or rate and the class of borrower, would reveal a significant amount about the actions of individual market participants.

AIMA members tend to borrow from a limited number of broker-dealers, which are publicly disclosed in Form ADV, says Król. “The publication of this data would be valuable to market participants looking to front run or short squeeze market participants building a short position or reverse engineer the strategies of firms taking short positions, particularly when the long positions of firms are publicly available via Form 13F,” he adds.

More broadly, MFA’s Jennifer Han urges the SEC, in its efforts to provide near intraday pricing transparency for securities lending markets, to provide a clear delineation between reporting for wholesale and retail segments of the securities lending market. MFA members are designated as “retail market”, she notes, because they are reliant on their broker-dealers to borrow securities, under the umbrella of their brokerage account agreements, to facilitate settlement obligations for short sales. The SEC is misguided, she believes, in its attempt to develop a consolidated tape for two very different types of securities lending activities — the “wholesale market” and the “retail market” — which are governed by different contractual frameworks.

AIMA raises a similar point in its response to the SEC, noting that while the wholesale market lends itself to a standardised transparency regime, the retail market consists of complex transactions that are part of bespoke relationships with nuanced interrelated contractual terms — for example collateral, counterparty and term — that are often not finalised until end of day or later. “As a result, retail market transaction data would lead to non-comparable and often misleading data reported and disseminated publicly,” AIMA states.

Closing thoughts

In the two parts of this article, SFT has evaluated a cross-section of the potential benefits offered by the SEC’s proposed 10c-1 reporting regime and the industry’s recommendations for amendments to this trade reporting model.

Given the weight of open questions, it seemed likely that the SEC would need to reopen some points for further consultation — and this was confirmed on Friday 25 February, just a business day before SFT 297 is published, when the regulator said that respondents would have a further one month to share their comments. In the same breath, it also put forward a new proposal under Exchange Act Rule 13f-2 that aims to provide greater visibility, through aggregated short sale data, regarding the behaviour of “large short sellers”.

In refining the 10c-1 design, it seems likely that the SEC will need to give consideration to whether it should approve additional RNSAs. A number of respondents to the SEC consultation have questioned whether it is appropriate that FINRA should serve as sole RNSA for the 10c-1 reporting process.

Another possible option is that lending participants could report trades directly to the SEC, given the capability that the regulator has in place to receive EDGAR filings and to provide public dissemination of this data.

For reasons discussed, It is also likely that the SEC may extend the range of reporting agents that it will approve to support 10c-1 reporting.

In designing its 10c-1 reporting regime, the SEC aims to strengthen its ability to monitor systemic risk and the buildup of stress in the market. This involves building greater visibility across the lifecycle of a securities loan transaction, including transactions passing through key service intermediaries such as prime brokers and lending agents.

In doing so, the SEC’s proposal recognises that a broker-dealer may borrow as principal, but then makes an onward loan either to the end client (for example, a hedge fund) or internally to a trading desk within the bank — recording this activity in its stock record-based accounting systems and tracking its P&L across each step in this chain of transactions.

By identifying the prime broker as a lender as well as a borrower — and therefore requiring the PB to report its securities lending transactions, securities on loan and available for loan — this will potentially give the SEC greater visibility across PB lending activity and how these loans are used. For CSFME’s Ed Blount, this is a major step forward.

In advancing this proposal, the SEC applies an important requirement — stated in a footnote in the proposal document — that ‘each lender must know its borrower’. This, Blount believes, will help the SEC to monitor whether the loan is used for legitimate purposes — a Reg T purpose — and will provide early indication of illegal practices such as cum-ex trades. An overarching objective for the SEC, he notes, is to encourage firms that borrow and lend as principal to have a detailed understanding of their risk and to know their borrowers. This, he says, will be an important step to ensuring that the industry is clean and that risk, at enterprise and systemic level, within this sector is monitored and managed effectively.

The proposals, which were unveiled by the SEC under Exchange Act Rule 10c-1, require lenders to report the material terms of securities lending transactions to a registered national securities association (RNSA), along with details of securities on loan and available for loan.

The first part of this article, published two weeks ago in SFT 296, provides detail of the proposed 10c-1 reporting framework and the reaction of the industry during public consultation, which closed on 7 January.

It is noteworthy, as we go to press with this issue, that the SEC has voted to reopen public consultation, providing respondents with additional time to share their recommendations on the design of the Proposed Rule. This additional consultation window will extend until 1 April (or 30 days from its publication in the Federal Register, whichever is later), giving respondents roughly one month to file their comments.

This is broadly equivalent to the first round of public consultation, when the SEC put forward 97 questions in its consultation document but gave the industry just 30 days to respond. The decision on Friday to open a second consultation window is indicative of the strong body of feedback received during the first consultation period and the weight of unanswered questions raised by the initial 10c-1 design.

Under the proposed new rule, any person that loans a security on behalf of itself or another person will be deemed to be a “lender”, including banks, insurance companies and pension plans, and thereby required to report.

To track the transaction, the RNSA will be required to assign a unique transaction identifier to each reported securities lending trade. Under this Proposal, the RNSA will publish selected data relating to each transaction, along with any subsequent modifications. It will also publish aggregated data providing details of on-loan securities and securities that are available to loan.

Scope and (extra)territoriality

Respondents to the SEC consultation highlight that further clarification is needed regarding the territorial scope of the 10c-1 reporting obligation and, also, which transactions should be reportable.

Although the Proposed Rule states that ‘(a)ny person that loans a security on behalf of itself or another person’ has a reporting obligation, the Rule in its current form does not identify clearly whether it is the lender’s domicile, the security itself or a combination which brings a transaction into scope of the reporting regime.

By comparison, under the Securities Financing Transactions Regulation (SFTR) regimes in the EU and UK it is primarily the domicile of the transacting entities which determines the reporting obligations, such that an EU entity, or an EU based branch of a non-EU entity, is required to report (or the equivalent for UK application).

According to Adrian Dale, head of regulation, digital and market practice at the International Securities Lending Association (ISLA), ISLA was advised that up to 18 per cent of lender transactions in the US market are provided by funds outside of the US. This statistic implies that a considerable volume of activity may not be captured by the proposed regulation, pending clarity on scope and extraterritoriality.

When a regulator is driving for greater transparency, as the SEC is doing with 10c-1, ISLA indicates that it is important, as far as possible, that these regulatory provisions are fit for purpose worldwide. This demands co-operation and agreement between national supervisors. Without this, inconsistencies are likely to develop in how markets are regulated at national level which could create arbitrage opportunities and impair efforts to harmonise around common global standards.

Thomas Tesauro, president of Fidelity Capital Market — speaking on his company’s behalf as a principal lender, borrower, prime broker, lending agent and securities lending data provider — shares concerns that the extraterritorial scope of the Proposed Rule is not clear.

He also indicates that the Proposed Rule does not define accurately what it means to “loan a security”. Fidelity is one of a number of respondents to the 10c-1 consultation that urges the SEC to provide clear definition of when a securities loan is deemed to be “effected”, pointing out that in the marketplace a loan is not typically considered to be effected until the loan has been contractually booked and settled, which may be end-of-day or on T+1.

Lessons from SFTR

In 2013, the FSB published a report, Policy Framework for Addressing Shadow Banking Risks in Securities Lending and Repos, that set out recommendations to address financial stability risks relating to securities financing transactions (SFTs). These included recommendations for national supervisory authorities to improve data collection for SFTs, strengthening their ability to detect financial stability risks and to develop policy responses.

Given that the EU has implemented a trade reporting regime for SFTs through a phased implementation during 2020 and 2021, it is useful to explore whether the SEC can learn valuable lessons from the design, testing and implementation process for SFTR.

Speaking to SFT, ISLA’s Adrian Dale indicates that had there been a market standard data representation of securities lending prior to that regulation, SFTR’s implementation would have been significantly faster, it would not have required years of consultations and clarifications, and would not have demanded as much development effort by market participants. At the same time, it would have offered regulators a clean view of the relevant SFT markets.

ISLA recommends that the support of a market-derived data set should be considered, both to facilitate transparency proposals and to assist the market in its future development. The Association has been working with its members, and with the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) and the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA), to create a consensus-derived market data standard, the Common Domain Model (CDM), which has been widely discussed elsewhere in SFT. Dale indicates that ISLA has made itself available to the SEC to discuss any of these points, including development and wider application of the CDM.

The 10c-1 Proposed Rule appears to envisage a much ‘leaner’ reporting framework than SFTR, with 12 reporting fields in the current 10c-1 design, compared with 155 for SFTR.

SFT asked Fran Garritt, RMA director of securities lending and market risk, whether this ‘lean’ 10c-1 reporting template is suitable for meeting the SEC’s transparency objectives — and whether additional fields may need to be added to provide a more accurate picture in terms of pricing transparency. Read Fran Garritt's article in full here

Garritt responds that RMA does not favour adding additional fields to the 10c-1 template. “We believe the SEC will be able to capture all the pertinent information related to pricing transparency with the current proposal,” he says. “From RMA’s perspective, excess data fields add limited benefit considering the additional cost of sourcing and transmitting the additional fields.'' In making this point, Garritt reminds us that the scope of 10c-1 and SFTR are quite different. “10c-1 would implement statutory authority for rulemaking with respect to securities lending specifically,” he says, “while SFTR covers other kinds of transactions.”

For ISLA’s Adrian Dale, it seems highly likely that the SEC will need to add additional fields during implementation to achieve the full objectives that it intends through the reporting regime.

“Experience [from SFTR implementation] illustrated that the initial field template advanced by regulators to support the reporting process is unlikely, in practice, to be sufficient — and typically it will be necessary to add extra fields during the testing and implementation to capture any missing elements,” says Dale. As an example, additional fields may need to be added to capture ESG and sustainability considerations in lending strategy and collateral transfers.

With this in mind, ISLA has continued to host meetings since SFTR went live to find solutions to data issues. For example, its members continue to encounter issues with fields and events such as timestamps, settlement failure, trading venue, maturity date, fees and Legal Entity Identifiers (LEIs). Questions may also be driven by conflicts between primary regulation, subsequent regulatory clarifications, and market practice.

As illustration, Dale notes that SFTR only has one currency field, for example, even though there may potentially be different currencies for valuation, collateral, and billing, and this consequently requires some workarounds to communicate the required information. Although currency fields are not a good example for the US market, Dale indicates that this does highlight the potential drawbacks inherent in the historical approach to regulatory reporting.

Ed Blount, in his capacity as executive director of Advanced Securities Consulting, proposes an alternative to the SEC’s proposed 10c-1 design that will allow asset managers to report loans to an RNSA via a registry using a copy of the custodian’s records (fig 1).

Figure 1

Speaking to SFT, he advises allowing lenders to report from their own data trust — a database that could be serviced by custodians on behalf of lenders and which, potentially, could be managed on a permissioned blockchain.

Under the data trust arrangement (box below), asset managers will submit trade reports to the beneficial owners’ custodians and carrying brokers; and agent lenders will submit loan transaction details or delivery orders to the custodian, as they do currently. The custodian will then send a copy of designated master files to the data trust registry, marking this with a unique transaction identifier (UTI) generated by the custodian’s systems.

Data trust

Ed Blount and David Schwartz, from the Centre for the Study of Financial Market Evolution, outline the case for a data trust to support securities lending reporting

A data trust is an evolving mechanism for individuals to take the data rights that are set out in law (or the beneficial interest in those rights) and to pool these into an organisation, a trust, in which trustees would exercise the data rights conferred by the law on behalf of the trust’s beneficiaries. The central organising principle for every data trust is that the trustees are instructed to use the data assets for the owners’ exclusive benefit. The key features of a data trust are ownership and control.

Blount and Schwartz recommend that the 10c-1 reporting system outlined in the SEC’s proposal should be adapted to accommodate a data trust formed by beneficial owners in the securities lending industry. Although a data trust for securities lenders and borrowers would be an original application of the concept, Truata, the European Mastercard data trust, may provide a useful precedent. Truata was formed to anonymise customer transaction data for analysis and compliance with the EU’s consumer privacy regulations. Truata’s beneficiaries are competitors, just like securities finance market participants, so they rely on robust usage and encryption policies that make it difficult for owners to use the data as a weapon against one another.

If lenders were permitted to join together to form a data trust, Blount and Schwartz believe they could pool not just the information required by 10c-1, but also Know your Customer (KYC), proxy voting, ESG and other transaction data for their own benefit.

This would offer potential to produce all the publicly available data envisaged by the SEC, as well as a privileged dataset of highly confidential, shared analytics for the reporting lenders, who are expected to pay for the 10c-1 disclosure system.

Data vendors and fintechs would bid to service the registry database, enabling beneficial owners to benefit from the analytics provided by these vendors, as they do currently. Contractors would reformat records and facilitate 10c-1 reporting to the regulatory transaction repository, as today. The creation of a new, wider pool of data would also stimulate competition among data vendors – which is another SEC goal.

If, as a 10c-1 requirement, the SEC continues to require data on loan availability (see box on p 20), Blount believes this can be captured accurately by the data trust from the portfolio custodian’s master files. However, some beneficial owners are likely to insist on their LEIs being encrypted and inventory aggregated to avoid providing information that might tempt predatory traders.

Corrections and modifications to reported loans — as well as data on ‘locates’ — could also be reported from the custodian’s master files in the data trust.

According to Blount, at least US$100 million could be saved from the estimated US$375 million in projected start-up costs for 10c-1 reporting, given that custodians are connected to the lending agents and asset managers through a number of utility networks. Instead of the 409 data input pipelines to FINRA, as estimated in the proposal, Blount says that only two would be needed for lenders of participating asset managers.

In developing an effective reporting regime, ISLA’s Dale emphasises that it is important for financial regulators to keep a watchful eye on the opportunities extended by new technology and harmonisation.

From a technology standpoint, he suggests that a reporting system based on distributed ledger technology (DLT) may deliver a more effective solution than the current SEC 10c-1 design. In a DLT-based environment, trade and collateral data may be reconciled instantly by trading parties (or their reporting agents), providing financial regulators with a transparent, consolidated view of market pricing in near to real time in accordance with the goals of 10c-1.

In implementing this solution, ISLA believes it is advisable to migrate to a DLT-based data repository, rather than adopting an intermediate solution — such as the SEC 10c-1 Proposal — that will consume resources and will potentially delay the adoption of an innovative DLT-based solution.

Delegated reporting

The SEC’s 10c-1 Proposal envisages a single-sided reporting regime that makes provision for reporting to be delegated to broker-dealers by lenders, subject to a written agreement. This currently appears to be the only form of delegated reporting permitted by the proposed rule. Beneficial owners that do not employ a lending agent or enter into a written agreement with a reporting agent would be responsible for complying with the requirements of the proposed rule themselves.

From a buy-side perspective, the Investment Company Institute (ICI) urges the SEC not to limit permitted lending agents to banks, clearing agencies, brokers or dealers for the purpose of meeting 10c-1 reporting. It should instead permit any lending agent that serves as an intermediary to a securities loan transaction to report on behalf of a beneficial owner, providing that it is able to satisfy the requirements defined by the Proposed Rule. “We believe that expanding the Rule in this manner would facilitate reporting by beneficial owners that prefer to use non-broker-dealer lending agents to report their securities loans,” say ICI’s associate general counsel Sarah Bessin, and Susan Olson, general counsel.

A broad set of reporting agents are supporting the SFTR reporting process in the EU and the UK — some of which are data or technology vendors and do not meet the SEC’s 10c-1 requirement of being a bank, agent lender or broker-dealer. Consequently, the SEC may wish to broaden its set of approved reporting agents, recognising that some lenders with international activities may prefer to utilise the same agents to manage their 10c-1 reporting in the US.

For Sharegain’s CEO Boaz Yaari, it does not follow that, just by virtue of being a broker-dealer, an entity will have the technological capabilities to meet the reporting challenges under the Proposed Rule. Therefore, where such technology capabilities exist, allowing Qualifying Technology Agents to act as reporting agents under Rule 10c-1 would ease the burden on broker-dealers and avoid concentrating the reporting services market.

Pirum indicates in its consultation response that the proposal to allow reporting to be delegated via a registered broker-dealer may create potential confidentiality and conflict of interest issues, as often the lenders subject to the reporting requirements will be engaged in securities lending with the same broker-dealers that they also use for transactions in the cash markets.

Without an alternative, Pirum believes, beneficial owners would either be forced to build their own direct reporting to RNSAs to mitigate these concerns, thereby significantly increasing their costs, or to exit the market entirely, thereby reducing overall liquidity.

Available-for-loan securities

SFTR in the EU and the UK requires two-sided reporting of SFT transactions with the objective of strengthening regulators’ and market participants’ ability to monitor risk across securities lending and financing activities.

However, in driving for greater transparency in securities lending markets, the SEC’s 10c-1 proposal requires that lenders report details of securities lending transactions on a trade-by-trade basis, and also provide additional information on securities that are on loan or available to loan.

As discussed more fully in part 1 of this article, this data for securities on loan and available for loan must be submitted to the RNSA by the end of each business day.

A number of respondents to the SEC consultation argue that the requirement to report available-to-lend securities should be removed from the reporting process.

The Risk Management Association states, for example, that requiring lenders to report securities that are available to lend “would provide little or no significant benefit for the securities lending market” — and this may potentially discourage lending and use of reporting agents.

RMA’s Fran Garritt and Mark Whipple, chair of the RMA’s Council on Securities Lending, point out that other securities finance transaction reporting regimes, particularly SFTR, do not require lenders to report data on available-to-lend securities. They propose that, in the case of 10c-1, more accurate estimates of loan supply could be extrapolated from fluctuations in trading volumes and fees that will also be available to the SEC through data that it aims to collect through the 10c-1 reporting regime.

Other observers note that the Proposed Rule mandates reporting of total on-loan balances, securities available to loan and the utilisation rate, but does so without regard to whether the lender has self-imposed restrictions on the number of securities or percentage readily available to loan. In this case, disclosing loan balances and utilisation rate, but without accounting for lender restrictions, is unlikely to provide a useful benchmark of availability.

Respondents from buy-side trade associations also raise concerns that the proposed 10c-1 reporting regime may reveal confidential information about members’ trading strategies.

Jennifer W Han, chief counsel and hedge of regulatory affairs at the Managed Fund Association (MFA), says that the MFA is “strongly concerned” that transaction-by-transaction financing data, even in anonymised form, would “provide the market with sufficiently detailed information to allow market participants to reconstruct or reverse-engineer investment and trading strategies, leading to situations similar to the GameStop and AMC market events.”

Jirí Król, deputy CEO and global head of government affairs at the Alternative Investment Management Association (AIMA), explains that even in anonymised form, these disclosures, specifically regarding the fee or rate and the class of borrower, would reveal a significant amount about the actions of individual market participants.

AIMA members tend to borrow from a limited number of broker-dealers, which are publicly disclosed in Form ADV, says Król. “The publication of this data would be valuable to market participants looking to front run or short squeeze market participants building a short position or reverse engineer the strategies of firms taking short positions, particularly when the long positions of firms are publicly available via Form 13F,” he adds.

More broadly, MFA’s Jennifer Han urges the SEC, in its efforts to provide near intraday pricing transparency for securities lending markets, to provide a clear delineation between reporting for wholesale and retail segments of the securities lending market. MFA members are designated as “retail market”, she notes, because they are reliant on their broker-dealers to borrow securities, under the umbrella of their brokerage account agreements, to facilitate settlement obligations for short sales. The SEC is misguided, she believes, in its attempt to develop a consolidated tape for two very different types of securities lending activities — the “wholesale market” and the “retail market” — which are governed by different contractual frameworks.

AIMA raises a similar point in its response to the SEC, noting that while the wholesale market lends itself to a standardised transparency regime, the retail market consists of complex transactions that are part of bespoke relationships with nuanced interrelated contractual terms — for example collateral, counterparty and term — that are often not finalised until end of day or later. “As a result, retail market transaction data would lead to non-comparable and often misleading data reported and disseminated publicly,” AIMA states.

Closing thoughts

In the two parts of this article, SFT has evaluated a cross-section of the potential benefits offered by the SEC’s proposed 10c-1 reporting regime and the industry’s recommendations for amendments to this trade reporting model.

Given the weight of open questions, it seemed likely that the SEC would need to reopen some points for further consultation — and this was confirmed on Friday 25 February, just a business day before SFT 297 is published, when the regulator said that respondents would have a further one month to share their comments. In the same breath, it also put forward a new proposal under Exchange Act Rule 13f-2 that aims to provide greater visibility, through aggregated short sale data, regarding the behaviour of “large short sellers”.

In refining the 10c-1 design, it seems likely that the SEC will need to give consideration to whether it should approve additional RNSAs. A number of respondents to the SEC consultation have questioned whether it is appropriate that FINRA should serve as sole RNSA for the 10c-1 reporting process.

Another possible option is that lending participants could report trades directly to the SEC, given the capability that the regulator has in place to receive EDGAR filings and to provide public dissemination of this data.

For reasons discussed, It is also likely that the SEC may extend the range of reporting agents that it will approve to support 10c-1 reporting.

In designing its 10c-1 reporting regime, the SEC aims to strengthen its ability to monitor systemic risk and the buildup of stress in the market. This involves building greater visibility across the lifecycle of a securities loan transaction, including transactions passing through key service intermediaries such as prime brokers and lending agents.

In doing so, the SEC’s proposal recognises that a broker-dealer may borrow as principal, but then makes an onward loan either to the end client (for example, a hedge fund) or internally to a trading desk within the bank — recording this activity in its stock record-based accounting systems and tracking its P&L across each step in this chain of transactions.

By identifying the prime broker as a lender as well as a borrower — and therefore requiring the PB to report its securities lending transactions, securities on loan and available for loan — this will potentially give the SEC greater visibility across PB lending activity and how these loans are used. For CSFME’s Ed Blount, this is a major step forward.

In advancing this proposal, the SEC applies an important requirement — stated in a footnote in the proposal document — that ‘each lender must know its borrower’. This, Blount believes, will help the SEC to monitor whether the loan is used for legitimate purposes — a Reg T purpose — and will provide early indication of illegal practices such as cum-ex trades. An overarching objective for the SEC, he notes, is to encourage firms that borrow and lend as principal to have a detailed understanding of their risk and to know their borrowers. This, he says, will be an important step to ensuring that the industry is clean and that risk, at enterprise and systemic level, within this sector is monitored and managed effectively.

NO FEE, NO RISK

100% ON RETURNS If you invest in only one securities finance news source this year, make sure it is your free subscription to Securities Finance Times

100% ON RETURNS If you invest in only one securities finance news source this year, make sure it is your free subscription to Securities Finance Times