Transparency works both ways — is 10c-1a the wrong type of transparency?

23 January 2024

Rule 10c-1a will increase transparency in the US securities lending market but not necessarily in the ways everyone wants or anticipates, says Broadridge's Martin Walker, head of product management at SFCM, and Valarie Thorgerson, senior director of product management

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

A chief data officer at a bank once told us she was going to create a data lake, where data scientists could use data goggles to look for insights. This may sound like the worst of management speak and the proposed data lake project may have been a failure, but it did contain a genuine insight. Simply having more data does not guarantee better decision making. The data needs to be in a usable format and those using the data need to understand the context of the data to use it effectively.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has been very clear about its objectives in introducing the compulsory reporting of securities lending transactions under Rule 10c-1a. It sees an urgent need to improve transparency in securities lending.

“The gaps in securities lending data render it difficult for end borrowers and lenders alike to ascertain market conditions and to know whether the terms that they receive are consistent with market conditions. These gaps also impact the ability of the Commission, registered national securities associations (RNSAs) and other self-regulatory organisations (SROs), and other Federal financial regulators, to oversee transactions that are vital to fair, orderly and efficient markets.”

The European Union’s equivalent rule, the Securities Financing Transactions Regulation (SFTR) mentions transparency 31 times. The final version of the SEC’s equivalent rule, 10c-1a, mentions transparency 353 times.

However, some market participants still claim that 10c-1a may introduce the “wrong type of transparency”. Different loans for the same security booked at the same time can have significantly different rates for a variety of reasons. These include the credit rating of the lender, the type of collateral provided, the stability of supply (i.e. the tendency of the lender to recall securities) and efficiency of the parties’ operational processes. Context is very important to make sense of market data in an area such as securities lending.

The lessons from SFTR

In terms of increasing transparency, SFTR has arguably been, if not a failure, a grave disappointment. Though reporting under SFTR started in 2020, it has so far had little impact on transparency in the EU and UK securities finance markets. Data quality for SFTR is a major issue as unusable data certainly would be the wrong type of transparency. Anecdotal evidence suggests regulators can make little use of the data. An analysis performed last year by regulatory reporting consultants Kaizen stated:

“Our SFTR testing experience indicates that there is a sea of price unit errors, haircut issues, incorrect quantity, incorrect price, incorrect type, under-reporting (collateral, re-use, cash reinvestment and funding sources) among a litany of other errors. On top of that, many aspects of SFTR remain only partially defined or undefined, such that the resultant data is of dubious value, full of uncertainty and contradiction.”

The reporting rules imposed under SFTR are inherently harder to comply with than those under 10c-1a. Up to 155 fields have to be reported for each trade and trade event. Both parties to a trade have to report it, leading to reconciliation issues. In comparison, a much higher degree of pragmatism went into drafting 10c-1a. For one thing, only 12 core data points are required. Sometimes less really is more because the dozen fields required by the SEC are the fundamental trade fields. The SEC, as explained at length in the final version of the rule, took on board much of the industry feedback, notably moving to end of day reporting and dropping requirements that would have been impossible to meet with existing infrastructure.

Comparison to existing market data sources

Some vendors already provide market data on an intraday basis, though the SEC in general has been critical of the completeness and accuracy of data provided by vendors.

“...currently available data on the securities lending market are incomplete, as private vendors do not have access to pricing information that reflects all transactions. This, in part, reflects the voluntary submission of transaction information by subscribers to vendors and is compounded by the uncertain comparability of data due to, among other things, the variability of the transaction terms disseminated, as well as how those terms are defined.”

Most data vendors providing market data available intraday do so at an additional cost. Firms willing to pay the extra costs and potentially source market data from multiple data vendors already have a more timely set of data than what will be available from 10c-1a. Even if it is less complete.

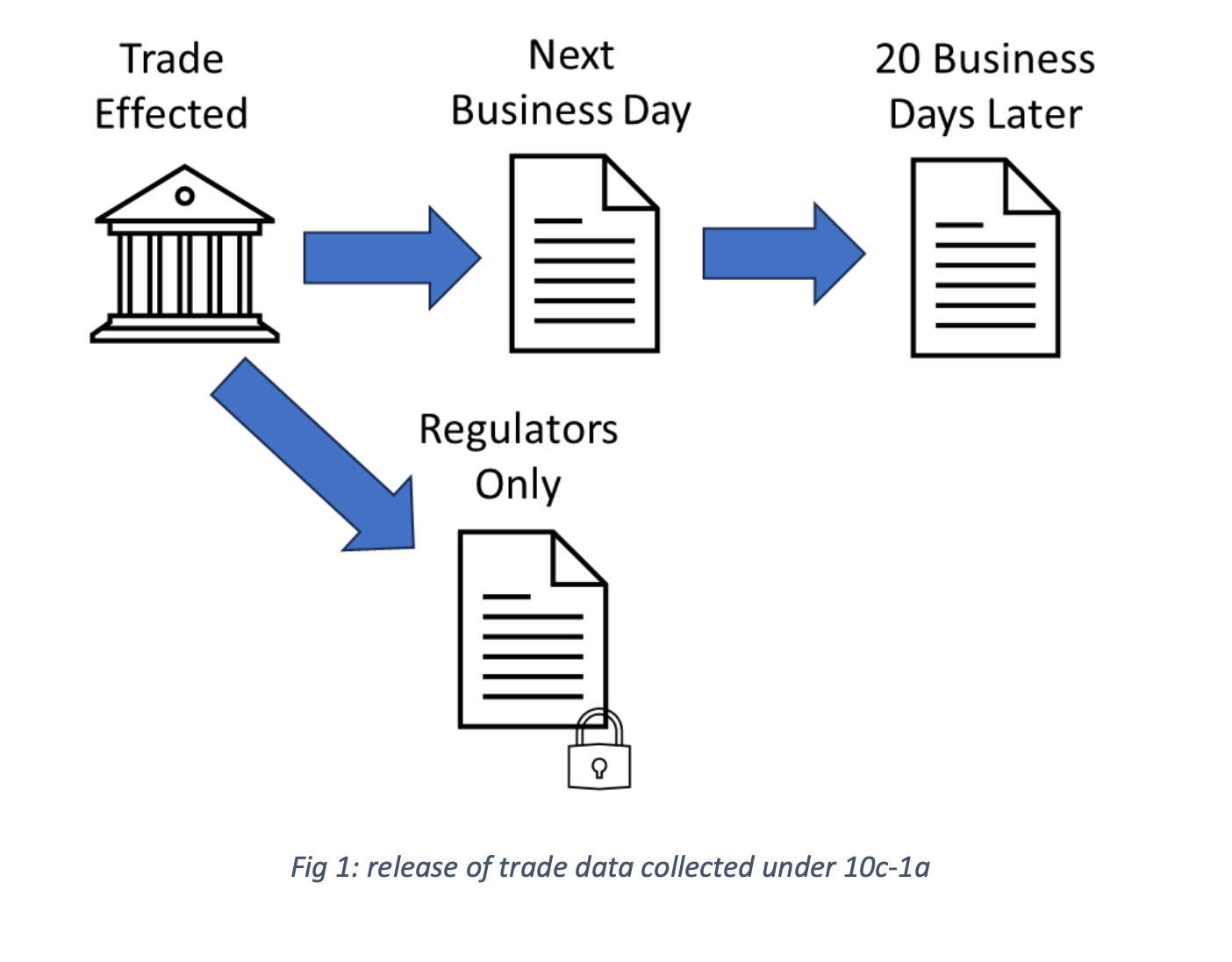

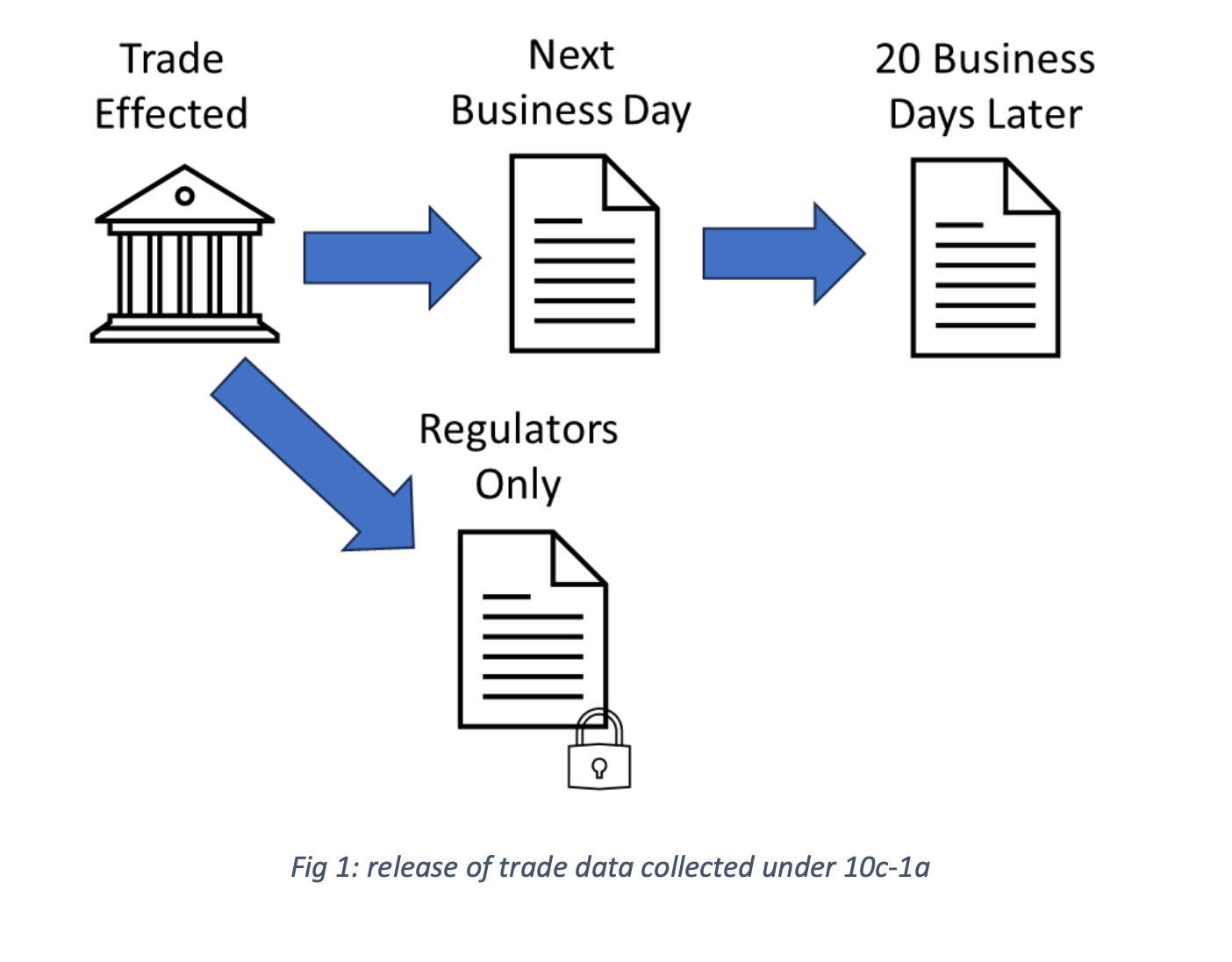

The regulation requires the relevant RNSAs to release the following data by the morning of the business day after the trade is effected:

• the unique trade identifier (UTI) assigned to a covered securities loan by RNSA

• the security identifier

• all other data elements, except for the loan amount

• aggregate transaction activity and the distribution of rates among loans and lenders (distribution of loan rates) for each reportable security

The RNSA is also required to make publicly available any modification to the data elements, except for modification to the loan amount, on the morning of the first business day following the modification.

Twenty business days after the loan is effected, the RNSA must release the securities quantities for each of the trades. This is to avoid releasing too much information about the trading positions of short sellers that have borrowed stock to cover shorts.

Fig 1: Release of trade data collected under 10c-1a

Certain data elements are only available to regulators and SROs, including:

• the legal names of the parties to the loan

• when the lender is a broker-dealer, whether the security is loaned from the broker-dealer’s inventory

• whether the loan will be used to close out a fail within the scope of Rule 204 of Regulation SHO or whether the loan is being used to close out a fail outside the scope of Regulation SHO

Note: There will be many times where the lender will never know if the loaned positions were due to Regulation SHO or fails on the receiving (borrower) side.

The time delays in disclosing data means that some of the larger firms are likely to continue paying for intraday data. The playing field will not be completely levelled for all participants and 10c-1a will not contribute to speeding up the overall operation of the securities lending market. The securities lending world will still be a long way behind the US cash equities market, which has the consolidated tape — a high-speed, electronic system that reports the latest price and volume data on sales of exchange-listed stocks.

Perhaps the securities lending market will never reach that level of transparency unless compulsory clearing, standardised collateral and fixed term trades remove the variables that can lead to different rates being agreed for the same security by different counterparties.

Impact of transparency

10c-1a will mean that beneficial owners of stocks, whether they lend through an agent or via a fully paid lending programme, will get an indication of how well their agents or brokers are working on their behalf. Those beneficial owners directly lending their securities will be able to see how the rates they receive compare to the market levels. In designing the regulation, the SEC has considered the context problem, raised by “wrong type of transparency” critics. One of the key pieces of data that will be made publicly available on the morning after trades is a distribution of loan rates, i.e. the range of rates for a given security. The SEC explained why in their final version of the rule:

“Information about the distribution of loan rates recognises that the cost-to-borrow securities can be influenced by a number of factors and can give market participants information to help compare the pricing of their loan against other loans.”

Perhaps this is not the perfect solution to the context problem, but any lender will be able see how well they are being rewarded for lending out their stocks, even taking into consideration other factors that can influence rates — are they receiving average returns? Above average or below average? This will inevitably lead to some difficult conversations and, if the SEC’s intentions are fulfilled, a more competitive market.

There is a potential downside to beneficial owners, since for many securities there is already an oversupply for lending purposes. Will agent lenders become choosier about who they add to their lending programmes? Beneficial owners may benefit from more keenly priced specials but lose revenue on other securities.

Another area where the drive for transparency may have an impact is from the data fields that will not be publicly released — notably the source of lent securities and the relation between lending activity, Regulation SHO and fails. Providing this type of information accurately and in a timely manner will require a joined-up system infrastructure that ideally integrates trading, inventory management and fails management.

Even with end of the day reporting deadlines, manual processes that integrate these types of data are likely to be impractical. Though the temptation will be to simply try to achieve compliance with 10c-1a by investing in trade reporting infrastructure, a wiser investment would be initially to look at their overall set of systems and business processes related to generating the complete set of data that needs to be reported. Getting those right, and providing transparency to regulators, should be relatively painless. If participants start trade reporting with unresolved issues in these areas, it really could turn into the wrong kind of transparency.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has been very clear about its objectives in introducing the compulsory reporting of securities lending transactions under Rule 10c-1a. It sees an urgent need to improve transparency in securities lending.

“The gaps in securities lending data render it difficult for end borrowers and lenders alike to ascertain market conditions and to know whether the terms that they receive are consistent with market conditions. These gaps also impact the ability of the Commission, registered national securities associations (RNSAs) and other self-regulatory organisations (SROs), and other Federal financial regulators, to oversee transactions that are vital to fair, orderly and efficient markets.”

The European Union’s equivalent rule, the Securities Financing Transactions Regulation (SFTR) mentions transparency 31 times. The final version of the SEC’s equivalent rule, 10c-1a, mentions transparency 353 times.

However, some market participants still claim that 10c-1a may introduce the “wrong type of transparency”. Different loans for the same security booked at the same time can have significantly different rates for a variety of reasons. These include the credit rating of the lender, the type of collateral provided, the stability of supply (i.e. the tendency of the lender to recall securities) and efficiency of the parties’ operational processes. Context is very important to make sense of market data in an area such as securities lending.

The lessons from SFTR

In terms of increasing transparency, SFTR has arguably been, if not a failure, a grave disappointment. Though reporting under SFTR started in 2020, it has so far had little impact on transparency in the EU and UK securities finance markets. Data quality for SFTR is a major issue as unusable data certainly would be the wrong type of transparency. Anecdotal evidence suggests regulators can make little use of the data. An analysis performed last year by regulatory reporting consultants Kaizen stated:

“Our SFTR testing experience indicates that there is a sea of price unit errors, haircut issues, incorrect quantity, incorrect price, incorrect type, under-reporting (collateral, re-use, cash reinvestment and funding sources) among a litany of other errors. On top of that, many aspects of SFTR remain only partially defined or undefined, such that the resultant data is of dubious value, full of uncertainty and contradiction.”

The reporting rules imposed under SFTR are inherently harder to comply with than those under 10c-1a. Up to 155 fields have to be reported for each trade and trade event. Both parties to a trade have to report it, leading to reconciliation issues. In comparison, a much higher degree of pragmatism went into drafting 10c-1a. For one thing, only 12 core data points are required. Sometimes less really is more because the dozen fields required by the SEC are the fundamental trade fields. The SEC, as explained at length in the final version of the rule, took on board much of the industry feedback, notably moving to end of day reporting and dropping requirements that would have been impossible to meet with existing infrastructure.

Comparison to existing market data sources

Some vendors already provide market data on an intraday basis, though the SEC in general has been critical of the completeness and accuracy of data provided by vendors.

“...currently available data on the securities lending market are incomplete, as private vendors do not have access to pricing information that reflects all transactions. This, in part, reflects the voluntary submission of transaction information by subscribers to vendors and is compounded by the uncertain comparability of data due to, among other things, the variability of the transaction terms disseminated, as well as how those terms are defined.”

Most data vendors providing market data available intraday do so at an additional cost. Firms willing to pay the extra costs and potentially source market data from multiple data vendors already have a more timely set of data than what will be available from 10c-1a. Even if it is less complete.

The regulation requires the relevant RNSAs to release the following data by the morning of the business day after the trade is effected:

• the unique trade identifier (UTI) assigned to a covered securities loan by RNSA

• the security identifier

• all other data elements, except for the loan amount

• aggregate transaction activity and the distribution of rates among loans and lenders (distribution of loan rates) for each reportable security

The RNSA is also required to make publicly available any modification to the data elements, except for modification to the loan amount, on the morning of the first business day following the modification.

Twenty business days after the loan is effected, the RNSA must release the securities quantities for each of the trades. This is to avoid releasing too much information about the trading positions of short sellers that have borrowed stock to cover shorts.

Fig 1: Release of trade data collected under 10c-1a

Certain data elements are only available to regulators and SROs, including:

• the legal names of the parties to the loan

• when the lender is a broker-dealer, whether the security is loaned from the broker-dealer’s inventory

• whether the loan will be used to close out a fail within the scope of Rule 204 of Regulation SHO or whether the loan is being used to close out a fail outside the scope of Regulation SHO

Note: There will be many times where the lender will never know if the loaned positions were due to Regulation SHO or fails on the receiving (borrower) side.

The time delays in disclosing data means that some of the larger firms are likely to continue paying for intraday data. The playing field will not be completely levelled for all participants and 10c-1a will not contribute to speeding up the overall operation of the securities lending market. The securities lending world will still be a long way behind the US cash equities market, which has the consolidated tape — a high-speed, electronic system that reports the latest price and volume data on sales of exchange-listed stocks.

Perhaps the securities lending market will never reach that level of transparency unless compulsory clearing, standardised collateral and fixed term trades remove the variables that can lead to different rates being agreed for the same security by different counterparties.

Impact of transparency

10c-1a will mean that beneficial owners of stocks, whether they lend through an agent or via a fully paid lending programme, will get an indication of how well their agents or brokers are working on their behalf. Those beneficial owners directly lending their securities will be able to see how the rates they receive compare to the market levels. In designing the regulation, the SEC has considered the context problem, raised by “wrong type of transparency” critics. One of the key pieces of data that will be made publicly available on the morning after trades is a distribution of loan rates, i.e. the range of rates for a given security. The SEC explained why in their final version of the rule:

“Information about the distribution of loan rates recognises that the cost-to-borrow securities can be influenced by a number of factors and can give market participants information to help compare the pricing of their loan against other loans.”

Perhaps this is not the perfect solution to the context problem, but any lender will be able see how well they are being rewarded for lending out their stocks, even taking into consideration other factors that can influence rates — are they receiving average returns? Above average or below average? This will inevitably lead to some difficult conversations and, if the SEC’s intentions are fulfilled, a more competitive market.

There is a potential downside to beneficial owners, since for many securities there is already an oversupply for lending purposes. Will agent lenders become choosier about who they add to their lending programmes? Beneficial owners may benefit from more keenly priced specials but lose revenue on other securities.

Another area where the drive for transparency may have an impact is from the data fields that will not be publicly released — notably the source of lent securities and the relation between lending activity, Regulation SHO and fails. Providing this type of information accurately and in a timely manner will require a joined-up system infrastructure that ideally integrates trading, inventory management and fails management.

Even with end of the day reporting deadlines, manual processes that integrate these types of data are likely to be impractical. Though the temptation will be to simply try to achieve compliance with 10c-1a by investing in trade reporting infrastructure, a wiser investment would be initially to look at their overall set of systems and business processes related to generating the complete set of data that needs to be reported. Getting those right, and providing transparency to regulators, should be relatively painless. If participants start trade reporting with unresolved issues in these areas, it really could turn into the wrong kind of transparency.

NO FEE, NO RISK

100% ON RETURNS If you invest in only one securities finance news source this year, make sure it is your free subscription to Securities Finance Times

100% ON RETURNS If you invest in only one securities finance news source this year, make sure it is your free subscription to Securities Finance Times